The cost is not just the price of the car

Warren Buffett often describes buying a new car as one of the most expensive financial mistakes people make—not just because of the sticker price, but because of the opportunity cost. The moment you drive it off the lot, the car starts losing value, while the money you spent could have been invested in something that compounds wealth. Buffett himself avoids the hassle and depreciation hit by buying used cars and keeping them for years, while he channels his capital into assets that grow. His view is simple: every dollar tied up in a car is a dollar that’s not working for you.

With this idea in mind, lets examine a Thought Experiment of the actual cost of buying a car. For this thought experiment we will look at four different options.

The first three options: leasing, financing, and paying cash; are relatively straightforward ways of getting into a car. But the fourth option takes a different mindset. It’s inspired by the book Rich Dad, Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki, which I first read back in 2001. In that book, Kiyosaki explains that an asset is something that puts money in your pocket, while a liability is something that takes money out of your pocket. His key lesson was that the rich buy assets first and then use the cash flow those assets produce to buy the liabilities they want.

That idea stuck with me. Armed with it, I began focusing on buying dividend-paying stocks with the goal of eventually matching my car payment. In essence, my dividend stocks would make my car payment for me. It wasn’t instant—it took until the summer of 2005 before I had accumulated enough dividend-paying stocks to afford the car payment on the car I wanted: a used Nissan 350Z convertible. But when I did, it proved the concept. Option 4, then, is the “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” method of using dividend-paying stocks (assets) to afford the liability of a car.

With that philosophy in mind, let’s set some assumptions and compare all four approaches over a 12-year timeframe.

Assumptions for the Comparison

- Car Purchase Price: $40,000 (my 350Z example).

- Time Frame: 12 years (a realistic lifespan of ownership or 4 lease cycles).

- Depreciation: Car loses ~20% in year one, then ~10% annually, stabilizing at ~25% of original price after 12 years (≈$10,000 residual).

- Lease Terms: $450/month for 36 months, repeated 4 times over 12 years.

- Finance Terms: 5-year loan at 6% APR. Monthly payment ≈ $773.

- Cash Option: $40,000 upfront, no loan.

- The “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” Dividend Strategy: Dividend-paying stocks yield 4% annually. To cover a $773/month payment, you’d need about $232,000 invested. Portfolio could shrink (-2%/year) or grow (+6%/year) depending on market performance.

Option 1: Lease the Car

- Total Paid: $64,800 over 12 years (4 leases).

- Ownership: None.

- Net Cost: $64,800.

Coach’s Take: Leasing is all about convenience. You’re always in a new car, always under warranty, and never committed long-term. But it’s pure consumption. Buffett would call this a wealth leak: you never build equity, and you sacrifice 12 years of compounding for the sake of a shiny upgrade every 36 months.

Option 2: Finance the Car

- Monthly Payment: ≈ $773 for 5 years.

- Total Paid: ~$46,400 (including ~$6,400 in interest).

- Car Value After 12 Years: ≈ $10,000.

- Net Cost: ~$36,400.

Coach’s Take: Financing is the middle ground. You spread out the purchase, absorb some interest, but you eventually own the car outright. For 7 of the 12 years, you drive “payment-free.” Compared to leasing, you save nearly $30,000 over 12 years. Buffett would still say: that $773/month could have been compounding into a six-figure sum, making the real cost much higher.

Option 3: Pay Cash

- Upfront Cost: $40,000.

- Car Value After 12 Years: ≈ $10,000.

- Net Cost: ~$30,000.

Coach’s Take: On paper, this is the cheapest option. No interest, no payments, full ownership from day one. But Buffett would caution: tying up $40,000 in a depreciating asset robs you of opportunity. If invested at a modest 7% annual return, that $40,000 could grow to over $90,000 in 12 years. In that light, your “$30,000 net cost” car may have really cost you more than twice that.

Option 4: The “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” Dividend Strategy

This mirrors the approach I used back in 2005. After years of deliberately building up a portfolio of dividend-paying stocks, I accumulated enough dividend income to cover the car payment on the 350Z convertible I bought. While I made the car payment itself from my Army paycheck, I also earned the same amount (or slightly more) from the dividend paying stocks I owned in my brokerage account. The dividends nulled out the car payment. In theory the stocks made the payment for me. I saw it work for me personally for the entire 5 years of my loan. At the end, not only did I own the Nissan 350Z but my portfolio had grown as well (though admittedly, the portfolio could have lost money).

Applied to our thought experiment:

- Required Investment: ~$232,000 in dividend-paying stocks at a 4% yield.

- Dividends Cover Payments: ≈ $773/month (enough to finance a $40,000 car).

- Car Value After 12 Years: ≈ $10,000.

- Portfolio Value After 12 Years: Could range from ~$215,000 (low growth) to ~$383,000 (high growth).

- Net Position: You end the 12 years with a car and a dividend paying stock portfolio.

Coach’s Take: This is the wealth-builder’s option. Instead of letting liabilities drain your income, you first buy an asset that produces cash flow, then let that asset fund the liability. Even if the portfolio barely holds its value, you still have both the car and the capital base. At the high end, you’ve turned what most people see as a wealth drain into a wealth engine.

Comparison Snapshot

| Option | Total Paid | Car Value | Net Cost | Wealth Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lease | $64,800 | $0 | $64,800 | Highest cost, no equity |

| Finance | $46,400 | $10,000 | $36,400 | Balanced option, long-term value |

| Cash | $40,000 | $10,000 | $30,000 | Cheapest in raw cost, big opportunity loss |

| Dividend | $46,400* | $10,000 | $36,400* | Car + portfolio ($215K–$383K) |

*funded by dividends, not out-of-pocket.

The Buffett Lens: Opportunity Cost of Each Option

Warren Buffett would argue that the real cost of a car isn’t just what leaves your wallet. It’s the investment growth you gave up by tying money into a depreciating liability instead of an appreciating asset. Let’s assume a modest 7% annual return (close to the long-term average of the stock market). Over 12 years, every $1 invested could more than double. Here’s how the four options look when viewed through that lens:

Option 1: Lease

- Out-of-Pocket Payments: $64,800 over 12 years.

- Opportunity Cost: If those payments had been invested instead, they could have grown to ≈ $112,000.

- Real Cost: $64,800 + $112,000 = ≈ $177,000.

Coach’s Take: Leasing doesn’t just cost you cash—it costs you the chance to build six figures in wealth.

Option 2: Finance

- Out-of-Pocket Payments: $46,400 over 5 years.

- Opportunity Cost: If those payments were invested instead, they could have grown to ≈ $80,000 by year 12.

- Residual Value: You still have a car worth ≈ $10,000.

- Real Cost: $46,400 + $80,000 – $10,000 = ≈ $116,400.

Coach’s Take: Financing is far better than leasing, but you still sacrifice nearly six figures in potential growth.

Option 3: Pay Cash

- Out-of-Pocket Payment: $40,000 upfront.

- Opportunity Cost: If invested at 7%, that $40,000 could have grown to ≈ $90,000 in 12 years.

- Residual Value: You still have a car worth ≈ $10,000.

- Real Cost: $40,000 + $90,000 – $10,000 = ≈ $120,000.

Coach’s Take: The cash option looks cheapest on paper, but opportunity cost makes it more expensive than financing.

Option 4: The “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” Dividend Strategy

- Out-of-Pocket Payments: $0 (covered by dividends).

- Opportunity Cost: You already invested $232,000 into dividend-paying stocks. If that portfolio compounds at 7% instead of 4%, it could grow to ≈ $522,000 in 12 years. With only 4% dividend yields, it might stay closer to ≈ $383,000.

- Residual Value: Car worth ≈ $10,000 + portfolio worth $215K–$383K.

- Real Cost: Your opportunity cost is the difference between 7% growth and 4% growth—roughly $140,000 in “lost upside.”

Coach’s Take: Still, you end up with both the car and a large investment portfolio. You don’t “lose money” the way you do in the first three options.

Side-by-Side Comparison (12-Year View)

| Option | Out-of-Pocket Cost | Opportunity Cost (7% growth) | Car Value Left | True Net Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lease | $64,800 | $112,000 | $0 | $177,000 |

| Finance | $46,400 | $80,000 | $10,000 | $116,400 |

| Cash | $40,000 | $90,000 | $10,000 | $120,000 |

| Dividend | $0 (dividends) | ~$140,000 (lost upside) | $215K–$383K + $10K car | Still net positive |

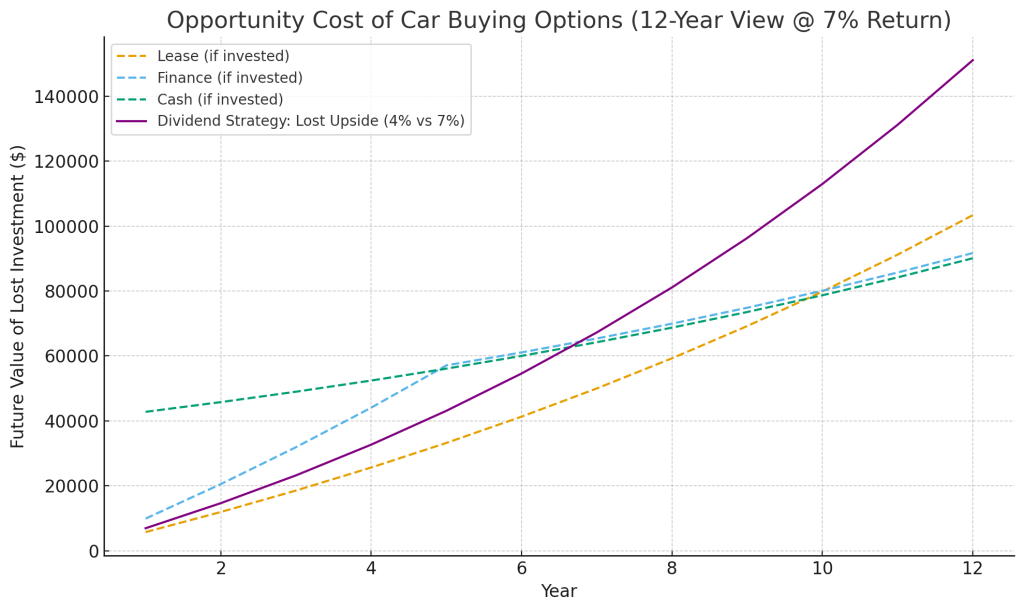

Opportunity Cost of Each Option – Graph

The opportunity cost analysis chart shows just how expensive a car can become once you look through Buffett’s lens. The dashed lines track what would have happened if the money spent on leasing, financing, or paying cash had instead been invested at a 7% return over the same 12 years. Leasing, with its steady stream of payments, represents the largest missed opportunity—by year 12, those dollars could have grown into well over six figures.

Financing, while cheaper in raw cost, still carries a heavy opportunity loss because the five years of payments could have compounded into significant wealth. Paying cash looks simple and frugal up front, but the chart reveals the hidden danger: that $40,000 lump sum could have doubled or more if invested, making the real cost far higher than the sticker price.

The purple line highlights the dividend strategy’s trade-off: by relying on 4% yields to cover car payments, you give up some upside compared to a 7% compounding portfolio—but unlike the other options, you still finish with both the car and a sizeable investment account. In short, the chart makes clear that the biggest expense isn’t the car itself—it’s the compounding wealth you forfeit depending on how you choose to pay for it.

Here’s the opportunity cost analysis chart:

- Dashed lines show how much wealth you could have built if the cash outflows from leasing, financing, or paying cash were instead invested at 7% over 12 years.

- Purple line shows the “lost upside” of the dividend strategy—the gap between a portfolio compounding at 4% vs. 7%.

Coach’s Closing Call

- Leasing is by far the worst. You lose cash and compounding.

- Financing beats cash when you include opportunity cost, though both are expensive long-term.

- Cash only looks cheapest until you add the “Buffett lens,” then it turns into one of the most costly.

- Dividend strategy is the only one that keeps you in the wealth-building game. Even with opportunity cost factored in, you end up with both a car and a growing portfolio.

Closing Whistle: The Real Game of Buying a Car

The “Buying a Car” thought experiment isn’t really about the car. It’s about the game plan you choose for your money. Leasing is like endlessly passing the ball across your back line: it looks active, but you never move forward, and at the final whistle you’ve got nothing on the scoreboard. Financing is the steady midfield play; yes, you absorb pressure early with those higher payments, but once the loan is behind you, you’ve got clear space and control of the game. Paying cash is like parking the bus on defense: safe, simple, and it keeps you in possession; but you’ve benched your best striker (your investment capital), which means you can’t score with compounding returns.

The dividend strategy, though, that’s the championship-level play. It’s like building a strong academy pipeline that produces talent year after year. Your assets generate the cash flow, those “players” score the goals, and suddenly the car payment is handled without pulling money out of your pocket. You get to keep both the car and the winning team on the field.

Buffett would call this the difference between just holding possession and actually converting chances into goals. The real cost of a car isn’t the sticker price; it’s the goals you didn’t score, the compounding wins you left on the bench. The wealthy understand this truth: build assets first, then let those assets fund your lifestyle. The lesson? When it comes to buying a car, don’t just think about today’s match. Play the full season with the championship in mind.