How Dollar-Cost Averaging Lets a Real Investor Ride the Curve

Introduction: From Thought Experiment to Real Behavior

In the first three parts of this series, we built a bridge step by step:

- Part I introduced the Farmer’s Compounding Garden. It showed what compounding feels like over a lifetime: painfully slow at first, then quietly unstoppable for those who stay long enough.

- Part II translated that story into financial principles. We focused on decades, doublings, the 25× rule, and the emotional cost of staying on the curve.

- Part III stress-tested the metaphor against real market data using a deliberately unnatural rule: buy one share per year regardless of price.

That last step mattered because it showed that, over 30 years, broad market ETFs such as DIA and SPY:

- broadly followed the curve of the Farmer’s Compounding Garden,

- lagged behind it for long stretches, and

- eventually caught up and often outperformed; but only after decades.

However, there is a problem.

Most real investors do not invest “one share per year regardless of price.” They invest dollars, not units. They put in the same contribution, or the same percentage of their pay, year after year.

That leads naturally to the next question in our thought experiment:

If we switch from “one share per year” to a “constant dollar amount per year,” does the market still look like the Farmer’s Compounding Garden?

And does this more realistic approach help or hurt the investor who is riding the compounding curve?

In this Part IV, we will examine exactly that by introducing a Dollar Cost Average Methodology and comparing it to both:

- the Farmer’s Compounding Garden, and

- the “Buy One Share Per Year” approach from Part III.

1. How Real Investors Actually Invest: Dollar-Cost Averaging

Most working investors do not sit down and say, “I will buy one share of DIA every December 31, no matter the price.”

Instead, the behavior looks more like this:

- “I will put $X per month into my 401(k).”

- “I will invest 10% of my paycheck into an index fund.”

- “Every year, I will contribute $Y to my IRA.”

This is Dollar-Cost Averaging (DCA). You invest the same dollar amount on a fixed schedule, regardless of the market price. When prices are low, your dollars buy more shares. When prices are high, your dollars buy fewer shares.

Over time, Dollar Cost Average tends to:

- smooth out the impact of volatility, and

- often leave you with more shares than simply buying one unit each year.

To compare Dollar Cost Average with the Farmer’s Compounding Garden and with the One-Share Method, we need to keep the total dollars invested roughly the same. That requirement led to an artificial, but very useful, construction.

2. Building a Fair Test: The Artificial Dollar Cost Average Setup

To keep this analysis as close to “apples to apples” as possible, we anchored Dollar Cost Average to the same total dollars invested under the “One Share Per Year” method over 30 years.

Here is how the Dollar Cost Average Methodology was built.

Step 1 – Total dollars from the One-Share method

From Part III’s “buy one share per year regardless of price” analysis, we know the total dollars invested over 30 years:

- DIA: $5,567.68 total over 30 years

- SPY: $6,644.16 total over 30 years

Step 2 – Compute the 30-year average dollar contribution

We divide those totals by 30 years to get a constant annual dollar amount:

- DIA average annual contribution: $185.59

- SPY average annual contribution: $221.47

You can think of these numbers as the “dollar equivalent” of the farmer’s one seed in the garden.

Step 3 – Invest those same dollars every year

Now we apply the actual Dollar Cost Average behavior:

- Each year, invest $185.59 into DIA and buy as many fractional shares as that dollar amount allows.

- Each year, invest $221.47 into SPY and do the same.

Some years, that contribution buys more shares because prices are low. Other years, it buys fewer because prices are high. Over 30 years, the total dollars invested are essentially identical to the One-Share method (within a few cents).

This construction is artificial in one key way:

- No investor in 1996 could have known, in advance, what the 30-year average cost per share would be.

- The average price is only knowable after the 30-year period has passed.

That limitation is acceptable here because the goal is not to provide a literal instruction set. The goal is to isolate the effect of the contribution style:

- same total dollars,

- same 30-year window,

- different rule for how shares are accumulated.

With this structure in place, we can ask the crucial question:

If you commit to steady, dollar-based investing over 30 years, how does your experience compare to the Farmer’s Compounding Garden?

3. What Dollar-Cost Averaging Actually Buys You

Under the One-Share method, you end the 30 years holding:

- 30 DIA shares, or

- 30 SPY shares.

Under the Dollar Cost Average methodology described above, with the same total dollars invested, you instead end up holding:

- 39.22755 DIA shares, or

- 42.48828 SPY shares.

That is a crucial difference.

Even with the same total dollars invested:

- Dollar Cost Average quietly assembles more shares than the “one share per year regardless of price” rule.

- This happens because Dollar Cost Average naturally buys more shares when prices are low and fewer when prices are high. In effect, it turns volatility from an emotional enemy into a mathematical ally.

In other words:

The investor who behaves like a real worker and invests steady dollars ends up owning more of the market than the investor who insists on buying a fixed number of shares every year.

The story does not end with “you get more shares.” The more important question is:

- How does that Dollar Cost Average value path compare to the smooth, calm curve of the Farmer’s Compounding Garden?

4. Benchmarking Against the Garden: Using the 30-Year Implied Growth Rate

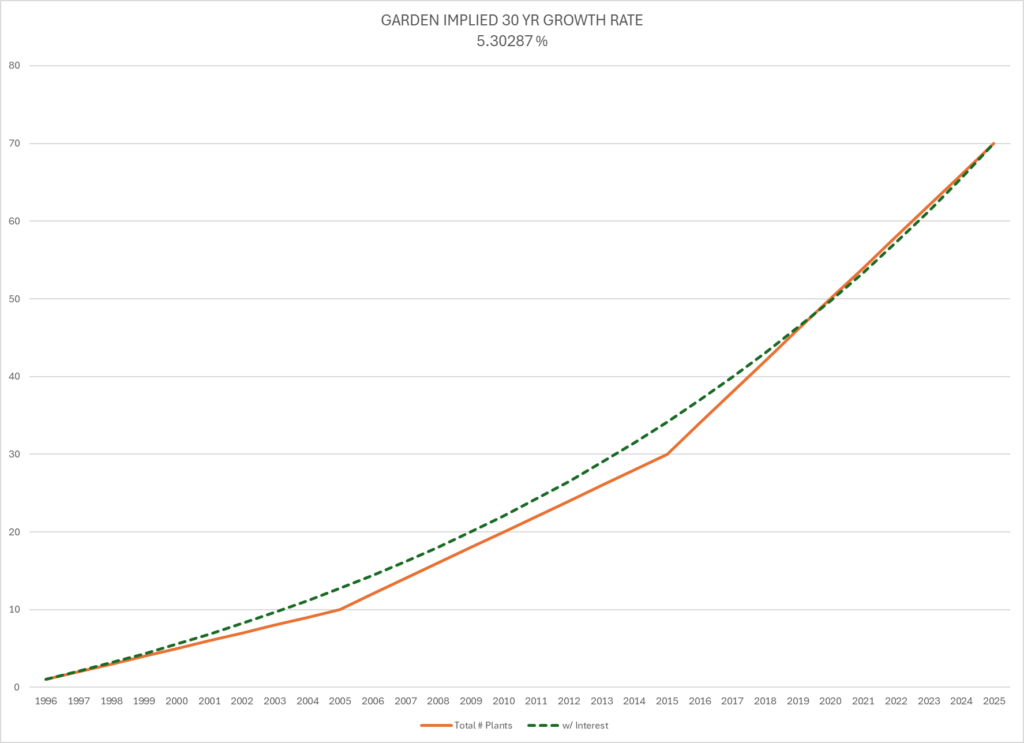

From earlier work on the Farmer’s Compounding Garden, we derived its overall 30-year implied growth rate. To grow from 1 plant in 1996 to 70 plants in 2025, the garden’s value behaves like a system compounding at about 5.3029% per year over that 30-year window.

Below is a graph that represents the actual number of seeds in the garden compared to a steady ~5.3% growth rate curve:

There is an important nuance here:

- Each individual seed in the garden doubles every 10 years, which is roughly 7.177% growth.

- The garden as a system adds one seed per year. When you measure the whole system, especially in earlier years, it exhibits a lower overall growth rate. Over 30 years, that implied rate is about 5.3029%.

- The approximate 5.3% growth curve overstates the total number of seeds in the Garden for 17 consecutive years (specifically between 2001 to 2017). But at each “tail”, the ~5.3% growth rate closely matches the total number of seeds in the Garden.

For this Part IV analysis, we treat that 5.3029% per year as the Garden’s 30-year “benchmark curve” and use this benchmark as our “proxy” to represent the value of the seeds in the Garden.

To make the comparison clean, we set:

- The Garden benchmark and the Dolar Cost Average investor to start at the same dollar value in 1996:

- DIA case: $185.59

- SPY case: $221.47

Each year, the Garden’s value grows by a smooth 5.3029%. The DIA or SPY Dollar Cost Average portfolio, by contrast, reflects the actual path of market prices as fractional shares accumulate.

This setup allows us to compare:

- A smooth, theoretical compounding curve (the Garden’s 5.3029% implied rate),

- To the real, jagged path of the market under Dollar Cost Average over 30 years.

Now we can examine what actually happens.

5. DIA vs the Garden: Patience, Underperformance, and a Late Surge

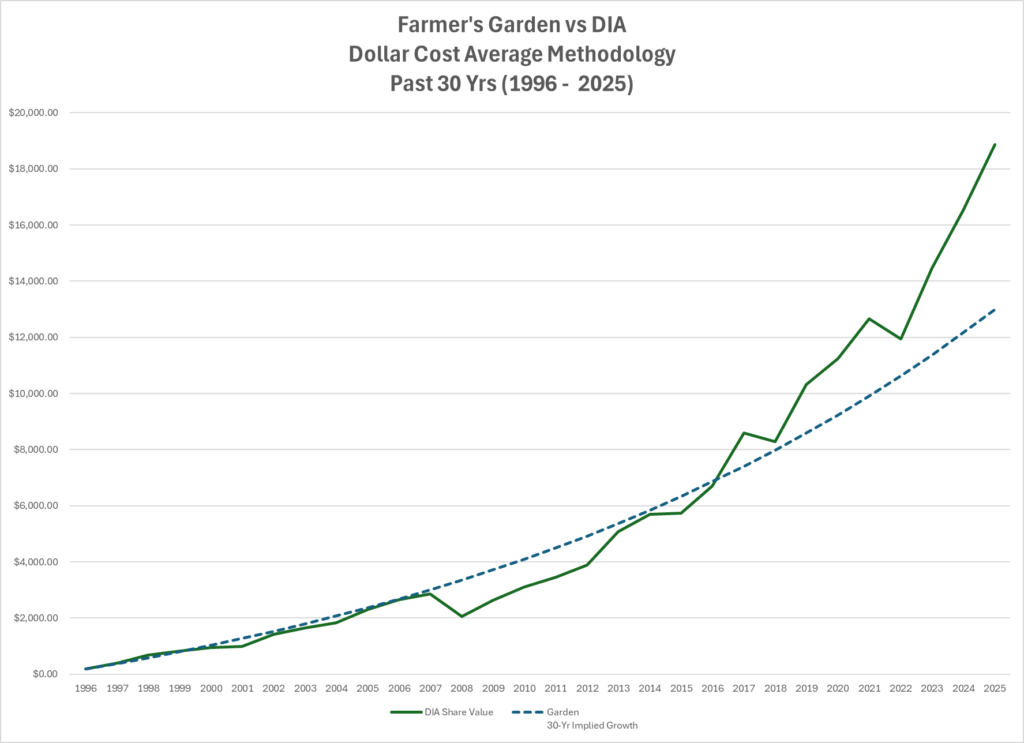

Below is the graph comparing the market’s (DIA) return to the Farmer’s Compounding Garden’s steady return of ~5.3%:

The DIA Dollar Cost Average results, compared to the Garden’s 30-year implied curve, reveal several important patterns:

- Pattern matching: DIA’s Dollar Cost Average value generally tracks the shape of the Garden’s curve. It oscillates around it, but it does not contradict it.

- Underperformance is common:

- In 17 out of 30 years, DIA underperforms the Garden.

- In 13 out of 30 years, it meets or beats the Garden.

- Decade checkpoints:

- After 10 years (1996–2005), DIA slightly underperforms the Garden.

- After 20 years (1996–2015), DIA still slightly underperforms the Garden.

- After 30 years (1996–2025), DIA outperforms the Garden.

- The long valley of doubt:

For 17 consecutive years (2000–2016), DIA’s Dollar Cost Average value remains below the Garden’s implied 5.3% curve. For almost two decades, an investor watching this position could reasonably feel that compounding “is not working as promised.”

Only after about 20 years does DIA begin to emerge from underneath the Garden’s curve and move into sustained outperformance. After 2019, the Dollar Cost Average methodology clearly pulls ahead.

Two conclusions stand out:

- Dollar-cost averaging does not spare you from long periods of underperformance relative to a smooth compounding benchmark.

- If you stay the course, DIA ultimately leverages its higher long-run returns and the extra shares accumulated by Dollar Cost Average to beat the Farmer’s Compounding Garden over the full 30-year span.

In simple terms, the Garden’s curve was not wrong. It was early. DIA just needed enough time for volatility, dividends, and underlying economic growth to express themselves through the Dollar Cost Average mechanism.

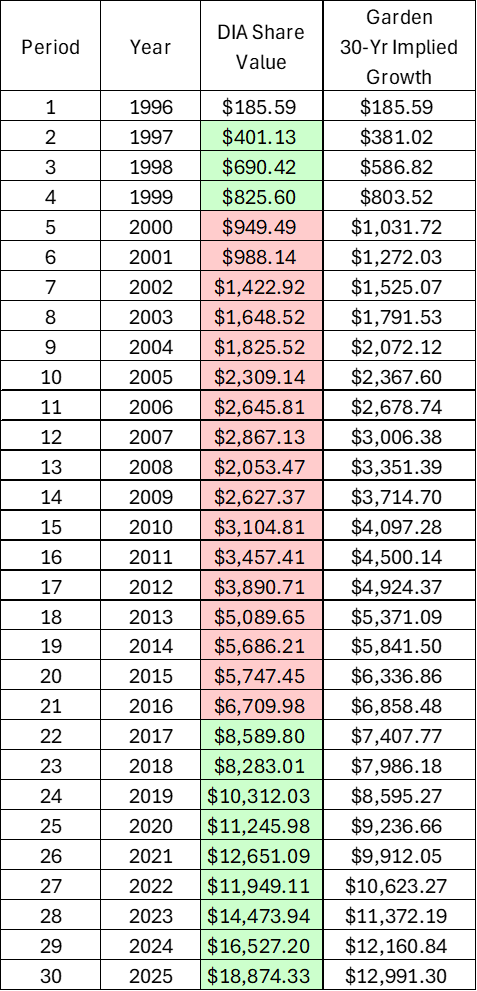

For those that want to see the numbers associated with the DIA vs. Garden graph, here is the Data Table:

For the above Data Table, DIA values highlighted in red underperform the Garden, while values highlighted in green outperform.

6. SPY vs the Garden: Same Story, Slightly Stronger Outcome

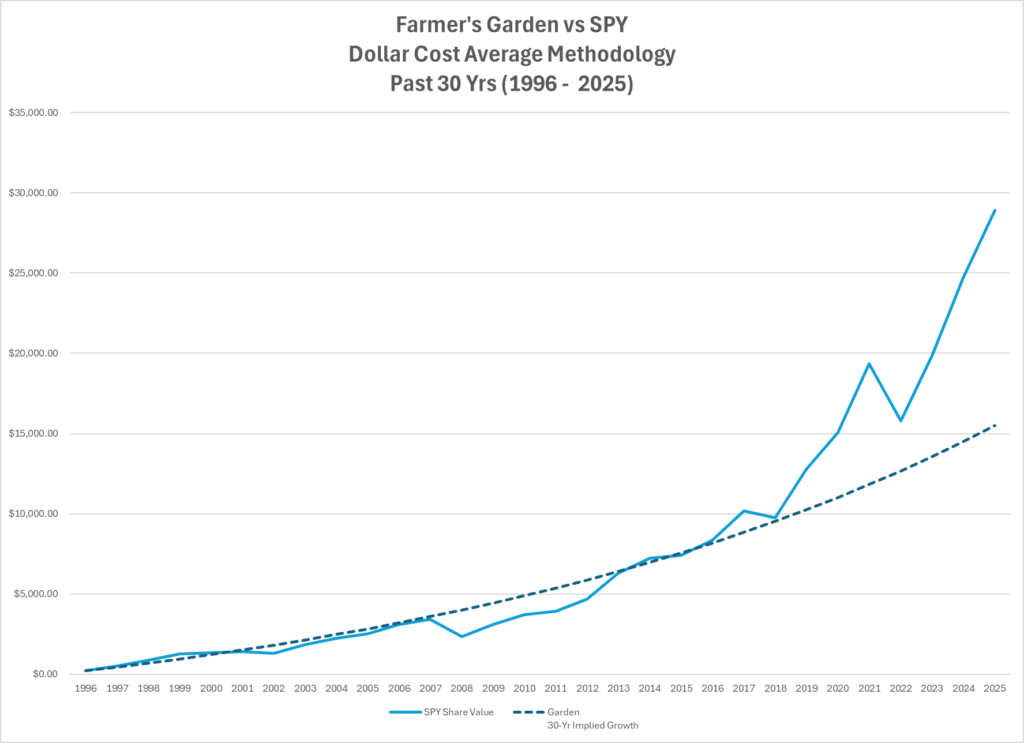

Below is the graph comparing the market’s (SPY) return to the Farmer’s Compounding Garden’s steady return of ~5.3%:

The SPY Dollar Cost Average case tells a very similar story with slightly stronger results:

- Pattern matching: SPY’s Dollar Cost Average value also generally follows the Garden’s curve, with its own jagged path above and below.

- Win–loss breakdown:

- In 16 of the 30 years, SPY meets or beats the Garden.

- In 14 of the 30 years, SPY trails the Garden.

- Decade checkpoints:

- After 10 years, SPY slightly underperforms the Garden.

- After 20 years, SPY still slightly underperforms the Garden.

- After 30 years, SPY outperforms the Garden.

- Extended underperformance:

For 13 consecutive years (2001–2013), SPY’s Dollar Cost Average value underperforms the Garden’s implied growth. During that time, an investor could easily conclude that the “promised” compound effect has failed them.

Once again, over more than a decade, the market makes compounding feel broken even while it is quietly setting up future outperformance.

As with DIA:

- The Dollar Cost Average returns gravitate toward the Garden’s curve, then eventually break above it.

- This clear outperformance does not appear until late in the journey, roughly past the 20-year mark and more visibly after 2019.

The lesson is direct:

Even when you use a behaviorally intelligent strategy such as Dollar Cost Average, the path to outperformance relative to a smooth compounding benchmark is long, uneven, and emotionally uncomfortable.

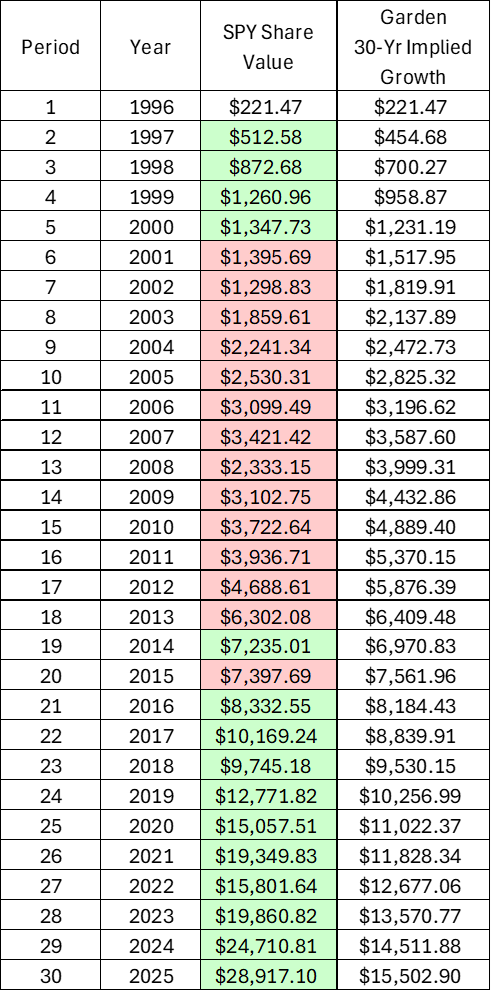

For those that want to see the numbers associated with the SPY vs. Garden graph, here is the Data Table:

For the above Data Table, SPY values highlighted in red underperform the Garden, while values highlighted in green outperform.

7. Dollar Cost Average vs One-Share: Turning Volatility Into an Ally

Now we compare the two market methodologies directly:

- Approach 1: Buy one share per year regardless of price (DIA-1, SPY-1).

- Approach 2: Invest the same dollar amount per year and let share count float (DIA-2, SPY-2).

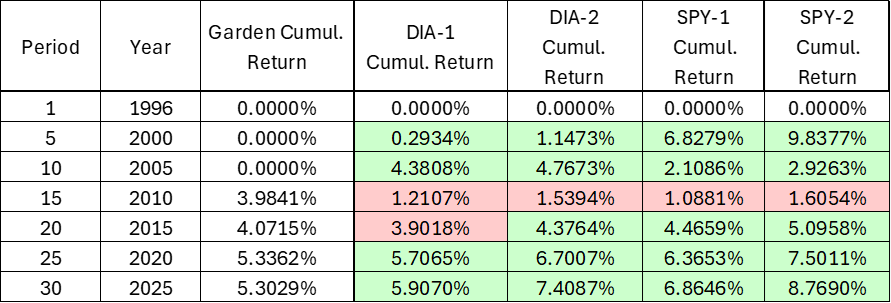

Below is a Data Table summarizing the Market returns compared to the Gardens implied growth rate for the year (or period) examined.

Returns highlighted in green outperform while returns highlighted in red underperform the garden’s implied growth rates for the year examined.

Using cumulative return checkpoints at Years 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30, a consistent pattern appears:

- In every single measured period, the Dollar Cost Average approach outperforms the “one share per year regardless of price” approach for both DIA and SPY.

By Year 30, for example:

- DIA-1 (one share per year): cumulative return of about 5.91%

- DIA-2 (Dollar Cost Average): cumulative return of about 7.41%

- SPY-1 (one share per year): cumulative return of about 6.86%

- SPY-2 (Dollar Cost Average): cumulative return of about 8.77%

- Regardless which approach you use (one share per year or Dollar Cost Average), either approach will outperform the Garden’s cumulative 30-year return of ~5.3%.

The total dollars invested are the same. The difference is purely in how and when those dollars translate into shares:

- The fixed-share method exposes you more sharply to sequence risk and to the path of prices.

- The Dollar Cost Average method naturally buys more shares when markets are down and fewer when markets are high, without any need to time the market.

Dollar Cost Average does not provide a smooth emotional ride. However, compared to the one-share method, it:

- uses the exact same dollars,

- produces more shares, and

- historically delivers higher long-term cumulative returns in this 30-year test.

Behaviorally, Dollar Cost Average converts volatility from something that scares you into something that quietly works for you.

8. What This Actually Means for You as an Investor

Here is how to translate all of this into your own financial life.

- The Farmer’s Compounding Garden remains a valid mental model.

Its 30-year implied growth rate of roughly 5.3% provides a reasonable benchmark for what a “steady compounding system” might produce when you combine work, savings, and investment over long horizons. - Dollar-cost averaging is the behavioral bridge to that Garden.

Most people cannot emotionally commit to perfectly timed lump sums. They can commit to a set dollar amount per month or year. Dollar Cost Average channels that ordinary, repeatable behavior into a mathematically coherent compounding system. - Dollar Cost Average outperforms the one-share-per-year method with the same dollars.

Over this 30-year window, Dollar Cost Average consistently beat the fixed-share method for both DIA and SPY because it:- bought more shares in cheap years,

- bought fewer shares in expensive years, and

- allowed volatility to enhance long-run share accumulation.

- Compounding still feels broken for long stretches, even with Dollar Cost Average.

You can use the “right” method and still experience:- 13 to 17 year windows of underperformance versus a smooth benchmark,multiple decades where your portfolio seems “behind schedule,” andclear and durable outperformance only in the third decade.

- Current outperformance may imply more modest future returns.

Both SPY and DIA, under Dollar Cost Average, sit well above the Garden’s ~5.3% implied curve after 30 years. This positioning suggests that the next 5 to 10 years may deliver more modest returns as the system regresses toward long-term averages. This is not a guarantee, but it is a reasonable expectation to hold loosely. The idea of regression to the norm deserves a deeper exploration, which we will address separately.

9. The Deeper Lesson: Method Matters, but Endurance is More Crucial

If you have followed this series from the beginning, you have now seen:

- A story in the Farmer’s Garden,

- A framework built on decades, doublings, and the 25× rule,

- A stress test using the One-Share-Per-Year method, and

- A behavioral upgrade through Dollar-Cost Averaging.

The central insight that shines through all of this is simple:

The method you use to invest matters. Your willingness to stay with that method for decades matters even more.

Dollar-cost averaging:

- does not eliminate discomfort,

- does not prevent drawdowns, and

- does not remove the emotional strain of long flat periods.

What it does provide is:

- alignment between your investing behavior and your income stream,

- automatic accumulation of more shares when markets are weak, and

- a stable platform that allows compounding to do its work over 20 to 30 years and beyond.

In the language of the farmer:

- Dollar Cost Average is a smarter, more human-friendly way of planting one seed’s worth of dollars each year, regardless of whether the season feels favorable or frightening.

Up Next: What if the Garden Is Ahead of Itself

We have now answered the core question for Part IV:

- The returns illustrated by the Farmer’s Compounding Garden are realistic when compared to real-world markets under a Dollar Cost Average methodology.

- Over 30 years, both DIA and SPY, using Dollar Cost Average, not only track the Garden’s implied curve but ultimately outperform it.

- The cost of that outcome is decades of discomfort, doubt, and apparent underperformance along the way.

In Part V, we will address the natural follow-up:

If the last 30 years have left the market ahead of the Garden’s curve, what should a long-term investor reasonably expect over the next 5 to 10 years?

We will use the 30-year, 50-year, and 10-year “double” curves that appear in the data to explore regression to the norm and what it might mean for someone who is still faithfully planting their financial seeds today. It is also described as “means reversion”: the long-run tendency of market returns to drift back toward their historical average after periods of unusually high or unusually low performance.